0xc129c981

Positive Policy Institute

The Ukrainian-Russian Conflict and its Impact on Global Energy Security

The Ukrainian-Russian Conflict and its Impact on Global Energy Security

In recent years, the world has witnessed a series of geopolitical events that have reshaped international relations and global markets. Among these, the Ukrainian-Russian conflict stands out, not only for its direct political and humanitarian implications but also for its profound impact on global energy security. Drawing from a comprehensive analysis of various authoritative sources, this article delves into the multifaceted consequences of the conflict on energy markets and the broader implications for global energy security.

- The Geopolitical Stage

Ukraine’s strategic position as a significant transit country for Russian gas exports to Europe has long been recognized. However, the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the subsequent conflict in Eastern Ukraine have intensified the geopolitical stakes, with energy security emerging as a central theme.

- Immediate Repercussions on Energy Markets

The conflict, while not directly about energy, has sent shockwaves through global energy markets. The immediate aftermath saw energy prices surge, with Russia standing to benefit significantly. By mid-year, Russia began to curtail gas supplies to certain countries, either for political reasons or payment disputes, further exacerbating the volatility.

- Europe at the Crossroads

Europe, which relies heavily on Russian gas, found itself at a crossroads. The immediate energy crisis led to inflation, economic downturns, and a palpable cost-of-living crisis. In response, European nations began to diversify their energy sources, turning to the Middle East and other regions, and exploring bilateral and multilateral energy deals.

- The Push for Alternative Energy

The conflict has inadvertently accelerated Europe’s transition towards a more sustainable energy future. By 2024, projections suggest that Europe could reduce its gas imports from Russia by a significant margin. This shift, while born out of necessity, aligns with global efforts to combat climate change and reduce carbon footprints.

- Broader Global Implications

The Ukrainian-Russian conflict underscores the intricate interplay between geopolitics and energy. As nations grapple with the immediate challenges, there’s a growing recognition of the need for a diversified energy portfolio. The war has catalyzed discussions on energy independence, the role of renewable energy, and the importance of international collaboration in ensuring energy security.

- Looking Ahead

As the world navigates the complexities of the 21st century, the Ukrainian-Russian conflict serves as a poignant reminder of the interconnectedness of global events. Policymakers worldwide face the dual challenge of ensuring energy security while also addressing the urgent threat of climate change. The lessons from this conflict will undoubtedly shape global energy strategies for decades to come.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment for Global Energy Diplomacy

The Ukrainian-Russian conflict, beyond its immediate geopolitical ramifications, has served as a watershed moment in global energy diplomacy. From an analytical vantage point, it’s evident that the world’s over-reliance on a few energy sources and suppliers is not just an economic risk but a profound geopolitical vulnerability. The conflict has exposed the fragility of global energy supply chains and underscored the urgency of diversification.

Furthermore, while the push towards alternative energy sources is commendable, it’s essential to recognize that such transitions cannot be reactionary. They require foresight, planning, and international collaboration. The reactive measures, although necessary in the short term, are not sustainable solutions.

It’s also worth noting that while Europe’s accelerated shift towards sustainability is a silver lining, it’s equally a stark reminder that global crises often force change more effectively than collective foresight. One can’t help but wonder: had there been a more aggressive push towards energy diversification and sustainability before the conflict, would the world be in a different position today?

In conclusion, the Ukrainian-Russian conflict is not just a lesson in geopolitics but a case study in the interplay between global events and energy security. As we move forward, it’s imperative for policymakers, researchers, and industry leaders to internalize these lessons and proactively shape a more resilient and sustainable global energy landscape.

References:

- CFR – Ukraine Conflict: Crossroads of Europe and Russia

- NY Times – Russia, Ukraine, NATO, and Europe

- The Conversation – Russia-Ukraine War’s Impact on Energy

- IEA – Russia’s War on Ukraine

- KPMG – How the Russia-Ukraine Crisis Impacts the Energy Industry

- IEA – The Impact of Russia’s Invasion on Global Energy Markets

- gov – The Energy Impact a Year After Putin’s Invasion

- Reuters – A Year After Russia Turbocharged the Global Energy Crisis

- CER – Impact of Ukraine War on Global Energy Markets

- Nature – What the War in Ukraine Means for Energy, Climate, and Food

- WEF – Russia-Ukraine War and Energy Costs

- IEA – Global Energy Review

- EIA – Europe’s Dependence on Russian Gas

- Brookings – Energy Security in Europe

- Atlantic Council – Europe’s Energy Transition

China, Culture, and Democratic Discourse: An Evolving Narrative

China, Culture, and Democratic Discourse:

An Evolving Narrative

China’s engagement with governance and democracy resembles an intricate silk tapestry, with each thread charting millennia of its storied past. The detailed embroideries spotlight the rich cultural motifs that have influenced its socio-political milieu, extending from the Great Wall’s imposing heights to the bustling urban landscapes of the south, bridging the wisdom of ancient Confucian scholars and the innovation of modern tech pioneers in Shenzhen.

The threads of this tapestry are multifaceted, sometimes harmonious, sometimes in contention. They recall epochs where divine mandates empowered emperors and eras when public sentiments demanded reform. They echo times when foreign entities sought inroads into China, through the duality of trade and conquest.

Analyzing this complex narrative demands dual lenses. The first, underscored by academic rigor, dissects events, ideologies, and influences with precision. The second is imbued with cultural sensitivity and humility, valuing the intricate nuances, deciphering symbolism, and understanding the weight of traditions, aspirations, and dreams shaping each stitch.

In our globally interconnected age, it’s imperative to comprehend that China’s tapestry is not static—it’s an evolving masterpiece, adapting as the nation navigates our collective global trajectory.

Historical Footprints:

China’s political evolution can be traced back to its ancient dynasties. Long before contemporary nation-states emerged, China had crafted a governance style melding centralized authority with an expansive bureaucratic system—a balance exemplified by the Tang and Qing dynasties, among others. This governance facilitated not just administrative prowess but also the flourishing of art, culture, and intellect. The Silk Road epitomizes China’s early global interactions, a pathway for both trade and cultural exchange. This era also witnessed the genesis of China’s political philosophies, infused with the tenets of Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism, which would subsequently mold governance paradigms for ensuing generations.

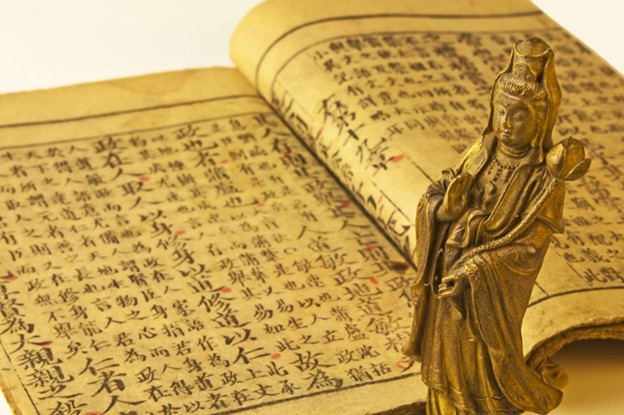

Cultural Complexities and Confucianism:

Confucianism, beyond being a philosophical tenet, has become a life compass for millions, profoundly influencing every stratum of Chinese society. Established by Confucius in the 5th century BCE, it extols values like righteousness and trustworthiness. The doctrine’s “Five Relationships” illuminate societal interactions and governance, delineating the dynamics between rulers and subjects, parents and children, and more. However, it’s pivotal to acknowledge that Confucianism’s interpretation and application have evolved over centuries, adapting to shifting socio-political contexts.

Interpreting the relationship between Confucianism and democracy mandates a nuanced approach. While Confucianism champions societal cohesion and the collective good, it doesn’t inherently negate democratic principles. The Confucian emphasis on meritocratic governance finds resonance with democratic aspirations. Moreover, nations with Confucian legacies, such as South Korea and Taiwan, affirm that Confucian values can harmoniously coexist with—and potentially fortify—democratic institutions.

The Quest for a “Chinese Democracy”:

China’s pursuit of its distinct governance paradigm is a reflection of its historical ethos and a solution to contemporary challenges. Dubbed the “Chinese model” or “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” this ideology aims to strike a balance between centralized governance and participatory elements. Central to this is the aspiration for societal harmony, deeply rooted in Confucian ideals.

By advocating a governance style that remains responsive to its citizens within a one-party framework, the Chinese leadership exemplifies this ethos. Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the late 20th century embody this synthesis of market forces with state oversight, blending economic dynamism with the quest for national rejuvenation.

While the modern Chinese state acknowledges Western democratic ideals, it often refracts them through its unique socio-political prism. In the Chinese context, “democracy” emphasizes collective welfare and stability over individual liberties. Hence, there’s a conscious recalibration of democratic principles to align with China’s cultural and historical fabric.

Contemporary Challenges:

China’s ascendancy on the global stage doesn’t negate its internal complexities. From economic disparities and environmental concerns to the intricacies of managing the world’s largest population, the challenges are multifarious. The digital revolution, while ushering economic windfalls, also raises concerns about information control, privacy, and cybersecurity.

China’s socio-cultural tapestry is intricate, with a multitude of ethnicities and cultures. Addressing the aspirations and concerns of ethnic minorities, particularly in regions like Tibet, Xinjiang, and the complexities of Hong Kong, remains a contentious endeavor.

A Global Conversation:

As China’s clout extends globally, its governance model not only presents an alternative but also prompts profound introspection about democracy’s essence. While some nations may be intrigued by the efficiency of the Chinese model, it’s crucial to acknowledge its diverse reception worldwide.

Global challenges—climate change, pandemics, technological upheavals—demand unparalleled cooperation. China’s responses, shaped by its governance model, will be pivotal. How the West harmonizes its democratic tenets with pragmatic collaboration with China remains an unfolding narrative.

Concluding Reflections:

China’s interplay with democratic principles, dissected through history, culture, and modern challenges, underscores the adaptability and resilience of political ideologies. In our quest to define governance, China serves as a poignant reminder that this journey is deeply human, transcending mere political dogma.

Governance models are ultimately tested by their ability to uplift their citizens. While critiques of China’s system abound, approaching this discourse requires empathy, open-mindedness, and a willingness to understand. Yet, introspection remains vital. China’s model, in all its nuances, poses fundamental questions for global democracies. As the 21st century advances, the unfolding Chinese narrative will undoubtedly be central to the global discourse on democracy.

References:

- Bell, Daniel A. The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy. Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Chan, Joseph. “Confucian Perfectionism: A Political Philosophy for Modern Times.” Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Dittmer, Lowell. China’s Continuous Revolution: The Post-Liberation Epoch, 1949-1981. University of California Press, 1989.

- He, Baogang. Rural Democracy in China: The Role of Village Elections. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Minzner, Carl. End of an Era: How China’s Authoritarian Revival is Undermining its Rise. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Nathan, Andrew J. “Chinese Democracy in 1989: Continuity and Discontinuity.” Problems of Communism, vol. 38, no. 5, 1989, pp. 37–50.

- Pei, Minxin. China’s Crony Capitalism: The Dynamics of Regime Decay. Harvard University Press, 2016.

- Schell, Orville and Delury, John. Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-first Century. Random House, 2013.

- Shirk, Susan L. The Political Logic of Economic Reform in China. University of California Press, 1993.

- Tsai, Kellee S. Capitalism without Democracy: The Private Sector in Contemporary China. Cornell University Press, 2007.

- Zheng, Yongnian. De Facto Federalism in China: Reforms and Dynamics of Central-Local Relations. World Scientific, 2007.

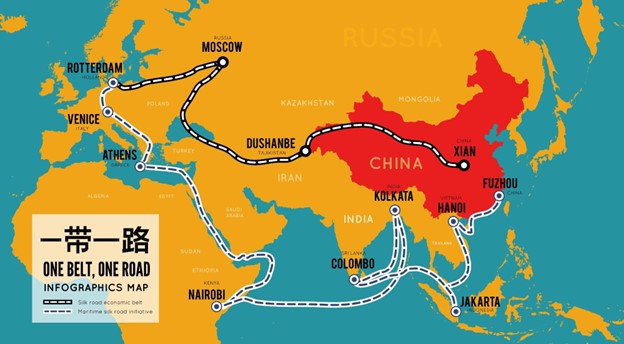

China’s Visionary Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, stands as a testament to the nation’s ambitious vision to reshape the global economic and geopolitical landscape. Drawing inspiration from the ancient Silk Road, this monumental project transcends mere infrastructure, encapsulating trade, policy coordination, financial integration, and cultural ties.

Economic Interdependence and Global Aspirations

At the heart of the BRI is the aspiration for a network of economic interdependence. Much like the post-WWII Marshall Plan, the BRI seeks to intertwine China’s economic ambitions with those of its partners, creating a framework for mutual development and shared benefits.

Origins, Imperatives, and Motivations

Emerging from a confluence of strategic foresight and economic necessity, the BRI aims to insulate China’s economy from external pressures, especially in the wake of the U.S.-China rivalry and the 2008 financial crisis. It reflects China’s multifaceted aspirations, both as an economic strategy and a symbol of its growing geopolitical influence.

Economic and Societal Implications

The BRI’s economic impact is vast, touching various sectors from infrastructure development, energy collaborations, and trade dynamics to financial integration. Beyond economics, the initiative promises societal advancements, from improved living standards and cultural exchanges to technological collaborations.

Environmental Stewardship and Considerations

With a commitment to green development, the BRI emphasizes environmental responsibility. Projects undergo rigorous environmental impact assessments, ensuring sustainability, judicious resource management, and collaborative conservation efforts.

Geopolitics, Regional Development, and the European Connection

The BRI’s vast scope intersects with the interests of global powers, especially in Europe and Russia. While it promises to transform China’s hinterlands into vital hubs, it also brings China closer to Europe, leading to both opportunities and apprehensions about China’s influence and the broader geopolitical implications.

Challenges, Risks, and the Path Forward

The BRI’s ambitious nature brings inherent challenges, from debt sustainability and governance issues to environmental concerns and geopolitical tensions. For the initiative to succeed, collaborative frameworks, debt management, environmental stewardship, and conflict resolution mechanisms are essential.

Conclusion

The Belt and Road Initiative represents China’s vision for a more interconnected, collaborative, and prosperous world in the 21st century. It is a testament to what can be achieved when nations come together with a shared vision and purpose. While challenges are significant, with careful planning, mutual respect, and a genuine commitment to shared benefits, the BRI has the potential to redefine global economic cooperation.

References:

- “The Belt and Road Initiative: China’s Vision for Globalisation”, Pacific Review, 2021.

- Wang, H. “Economic Implications of China’s Belt and Road Initiative”, Journal of Economic Structures, 2019.

- Zhang, Y. “Regional Development through Infrastructure Investment: The Case of BRI”, China Economic Journal, 2020.

- Lee, K. “The Belt and Road Initiative: Geopolitical Implications and Challenges”, Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 2021.

- Kaczmarski, M. “Russia-China Relations in Central Asia: Why Is There No Security Competition?”, International Affairs, 2018.

- Casarini, N. “Is Europe to Benefit from China’s Belt and Road Initiative?”, International Spectator, 2019.

- Summers, T. “China’s ‘New Silk Roads’: Sub-National Regions and Networks of Global Political Economy”, Third World Quarterly, 2016.

Ancient Chinese Thought on Foreign Policy: A Deep Dive into the Warring States Period

Ancient Chinese Thought on Foreign Policy

The Warring States period, spanning from 475-221 BCE, remains one of the most transformative eras in Chinese history. This epoch, marked by the rise and fall of numerous powerful states, was not merely a time of military conquests and political intrigue. It was also a fertile ground for intellectual and philosophical growth, leading to the crystallization of doctrines that would profoundly influence Chinese foreign policy for the subsequent millennia.

The Divine Mandate: Heaven’s Chosen Ruler

At the heart of ancient Chinese thought on foreign relations lies the revered concept of the “Mandate of Heaven.” This belief, deeply embedded in the Chinese cultural and spiritual fabric, posits that the ruler of China is not just a mortal sovereign but is divinely chosen to govern the vast nation. Their rule’s legitimacy is intrinsically linked to their ability to maintain societal order, ensure prosperity, and cater to the well-being of their subjects. Should they falter in these sacred duties, the divine mandate could be revoked, leading to potential upheavals and dynastic changes. This concept served a dual purpose: it provided a framework for governance and became a potent tool for justifying territorial expansions. The Chinese ruler, perceived as divinely appointed, was seen as having a celestial duty to bring harmony and order to the world, even if it necessitated the annexation of neighboring states.

The Dichotomy of Civilization: China and the “Barbarian”

Another pivotal concept that took root during this period was the distinction between the civilized Chinese and the “barbarian.” The Chinese, with their advanced institutions, rich cultural tapestry, and sophisticated societal structures, viewed themselves as the zenith of civilization. In contrast, the inhabitants of surrounding regions were often labeled as “barbarians” – entities that were perceived as culturally inferior and in need of guidance or control. This perspective transcended mere ethnocentrism; it became a driving force behind numerous military campaigns. The conquest, colonization, and subsequent Sinicization of neighboring territories were often portrayed as benevolent endeavors, aimed at bestowing the gift of Chinese civilization upon the unenlightened.

Tian Xia: Envisioning a World Under Chinese Hegemony

The philosophical notion of “Tian Xia,” which translates to “all under heaven,” further accentuates China’s perceived central role in the global order. This worldview envisaged the Chinese Empire as the world’s heart, with all other states, kingdoms, and tribes existing in a tributary relationship with the Chinese Emperor. Such a cosmological perspective provided a robust justification for Chinese expansionist ambitions. The empire, in its quest to bring order, civilization, and prosperity, saw itself as shouldering a divine responsibility to the world.

Confucianism: The Ethical Pillar of Foreign Relations

The teachings of Confucianism, emphasizing moral rectitude and ethical governance, played a pivotal role in shaping ancient Chinese thought on foreign relations. Confucian tenets advocate that rulers should govern with a blend of wisdom, compassion, justice, and a profound sense of duty. This philosophy, while primarily directed at domestic governance, also permeated foreign policy. The Chinese, under the aegis of Confucianism, believed that their expansionist endeavors were not mere acts of conquest but were missions to disseminate civilization, culture, and ethical governance to neighboring regions.

In Conclusion

The Warring States period, though replete with battles and political machinations, was also an era of profound philosophical introspection. The intricate tapestry of ancient Chinese thought on foreign relations, woven with threads like the Mandate of Heaven, the civilized-barbarian dichotomy, the “Tian Xia” worldview, and the ethical compass of Confucianism, laid a robust foundation for Chinese foreign policy. These deeply entrenched ideas, resonating through the annals of history, continue to shape China’s interactions with the world, offering a unique lens through which the nation perceives its global role.

References:

- Lewis, M. E. (2000). The early Chinese empires: Qin and Han. Harvard University Press.

- Fairbank, J. K. (1979). The Cambridge history of China. Cambridge University Press.

- Pines, Y. (2002). The Mandate of Heaven: History, Ritual, and the Early Chinese Empire. T’oung Pao, 88(4/5), 306-358.

- Mote, F. W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Harvard University Press.

- Hucker, C. O. (1975). China’s imperial past: An introduction to Chinese history and culture. Stanford University Press.

- Bodde, D. (1986). The state and empire of Ch’in. In The Cambridge History of China (pp. 20-102). Cambridge University Press.

- Pu, M. (2012). The barbarian and the Chinese view of the world. Journal of World History, 23(1), 1-18.

- Keightley, D. N. (1999). The Shang: China’s first historical dynasty. In The Cambridge History of Ancient China (pp. 232-291). Cambridge University Press.

- Di Cosmo, N. (2002). Ancient China and its enemies: The rise of nomadic power in East Asian history. Cambridge University Press.

- Zhao, T. (2009). Tianxia Tixi: History and Metaphor. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 76(1), 305-338.

- Wang, G. (2007). The Chinese worldview. China Intercontinental Press.

- Yao, X. (2000). An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press.

- Tu, W. M. (1985). Confucian thought: Selfhood as creative transformation. SUNY Press.

- Loewe, M., & Shaughnessy, E. L. (1999). The Cambridge history of ancient China: From the origins of civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press.

- Fairbank, J. K., & Goldman, M. (2006). China: A new history. Harvard University Press.

The Legacy and Impact of Jiang Zemin’s Passing

Introduction

The demise of Jiang Zemin, former President of China, on November 30, 2022, has sparked a myriad of responses both within China and internationally. His leadership, which spanned a crucial decade post the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, was marked by significant economic expansion and a somewhat paradoxical blend of openness towards international engagement and stringent domestic control. This analysis seeks to explore the multifaceted impact of Jiang’s passing, considering the current socio-political climate in China, and the legacy he leaves behind.

Jiang Zemin’s Leadership: A Dichotomy of Progress and Control

Jiang Zemin’s era was characterized by a dichotomy wherein economic liberalization and international cooperation coexisted with strict domestic control and suppression of dissent. His leadership saw China regaining control of Hong Kong, securing the opportunity to host the 2008 Summer Olympics, and notably, becoming a member of the World Trade Organization. These milestones symbolize China’s reintegration into the global community post-Tiananmen Square, for which Jiang is often credited.

Concurrently, Jiang’s regime also sowed seeds of systemic corruption and maintained a firm grip on one-party rule, suppressing political reform and dissent. His administration was notably responsible for the crackdown on the Falun Gong religious sect in 1999 and maintaining a hardline stance on Taiwan, reflecting a leadership style that balanced external amiability with internal authoritarianism.

The Timing of Jiang’s Death Amidst Current Protests

The timing of Jiang’s death is particularly poignant, coinciding with widespread protests against China’s stringent “zero-Covid” policy. Historically, the death of political leaders in China has sometimes served as a catalyst for public expression of dissent and demands for governmental change, as seen in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests following the death of Hu Yaobang. The current protests, coupled with the mourning of Jiang Zemin, could potentially amplify the citizens’ voices against the existing leadership, particularly against the current leader, Xi Jinping.

The Legacy and Symbolism of Jiang Zemin

Jiang’s legacy is undeniably complex and multifaceted. His leadership style, which blended a charismatic international presence with a stern domestic governance, has left a lasting impact on China’s global positioning and internal dynamics. His “Three Represents” theory aimed at modernizing the Communist Party, and his efforts to strengthen ties with the US, notably post the 9/11 attacks, showcased a pragmatic approach towards international relations.

However, the nostalgia for Jiang’s era, particularly among the younger generation who have caricatured him affectionately in internet memes, may be somewhat misplaced or romanticized. Critics, like Wang Dan, a student leader from 1989, label him as a “typical political opportunist” and a conservative political figure, highlighting the importance of critically evaluating the entirety of his leadership.

Conclusion: A Confluence of Past and Present

Jiang Zemin’s death and the subsequent public and governmental responses provide a lens through which the complexities and contradictions of his leadership can be viewed. His passing has the potential to serve as a pivotal moment in China’s current socio-political landscape, possibly amplifying existing public dissent and protests. The legacy he leaves behind is a tapestry of economic progress, international engagement, domestic control, and systemic issues, which will continue to shape China’s future trajectory in the global and domestic arenas.

As China mourns Jiang Zemin and navigates through the current socio-political challenges, the nation stands at a crossroads where the past and present converge, potentially influencing the path it takes into the future. The unfolding events post-Jiang’s passing will be crucial in determining whether his death will merely be a moment of reflection on a bygone era or serve as a catalyst for significant socio-political shifts in China.

Reference:

McDonell, S., & Wong, T. (2022, November 30). “Jiang Zemin: Former Chinese leader dies aged 96.” BBC News, Beijing and Singapore.

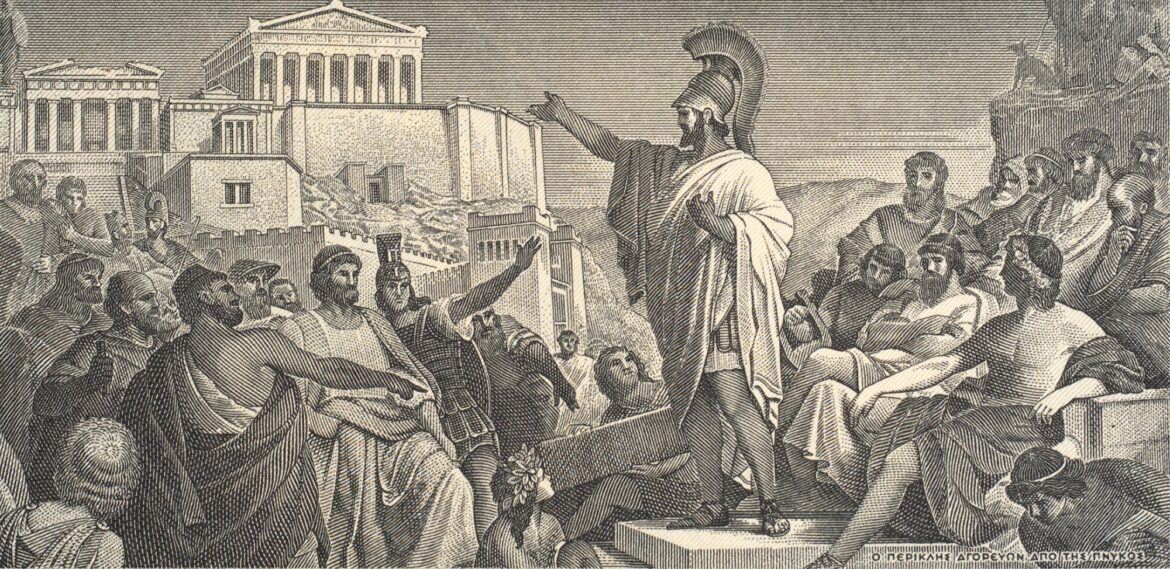

DEFINING DEMOCRACY

INTRODUCTION

Democracy is one of the most popular concepts in the field of political science. The popularity is at the same level in the real political arena as well. Both scholars and the political actors at different levels spend an endless effort to define, comprehend, express, reach and sustain a democratic system. In essence, it is this effort itself which merits explanation and understanding comprehensively.

Is it convenient to use the word “democracy” for the all the polyarchies which hardly have a common denominator and contain only one or two indicators referred in the definition of the term or should we draw a line and exclude once and for all the ones which fails to meet all the aspects of the definition? Is there a one stable definition of democracy to label the countries as democratic or nondemocratic? Why it is so important to define a political regime as democratic and to what extent can the definition of the concept be broaden? The answers, I think, is very closely related to the answer to another question: To what end of which political actor is the concept of democracy supposed to serve? In order to understand the practical need for the concept of democracy in the contemporary world via these questions, I would firstly like to brief the efforts to find a proper definition to the word “democracy”. Meanwhile, I will try to compare the components of the concept as used in the definition in theoretical level with the understanding of them in the actual political field. I also argue that the components of the definition is connected with the social culture as well. Hence, in the end I will reverse the view and try to see the effects of the culture to the definition of democracy.

CORE DEFINITION OF DEMOCRACY

In the simplest way, we can label a socio-political order as democracy if the governing bodies are established by the officials elected by the people through a voting procedure. In that sense, there are a few countries left in the world which are ruled by a nondemocratic government. However, the components of the definition are needed to be expanded in order to determine the common features of the systems on one hand and the authentic attributes changing from one country to another on the other hand.

The indicators of democracy are determined by Robert Dahl as elected officials, free and fair elections, inclusive suffrage, competition for governing, freedom for disseminating the ideas regarding the political system, chance to access alternative and accurate information and freedom for gathering and association. Some other requirements connected with those basic components such as the governing power and authority of the elected body, the sustainability of the multivocality, etc can be added to this rough definition. (O’Donnell, 1996) In other words, a range of variables can be derived to be included in or excluded from the definiton in line with the aim of the research or the political ideal. (Collier and Levitsky, 1997).

ELECTIONS AS THE MAIN CONCEPT IN THE DEFINION

Once we accept the country-wide elections are at the core of the definition of democracy, we automatically conclude that the ruling power is at the disposal of an authority which is not predestined to govern but required to compete and succeed in a rivalry to take the office. On the other hand, if an election system is to pave the way for a democratic order, it is expected to have certain qualifications. Firstly, the elections should be fair and free. If the aim is to learn the choices of the people, the voters reflects their opinions about politics free without feeling any threat to their physical, social or economic safety. Moreover, each person should has one vote, in other words every vote should be counted equally. Secondly, the suffrage is expected to be determined inclusively in a democratic order. The criteria for suffrage can be set according to age, gender, social status, position in the public service, criminality, nationality etc. For sure, the constraints regarding the political rights varies from one country to another due to the potential of the society. In this respect, the broader the proportion of the society allowed to take part in the electoral process is, the more the preferences of the majority of the people to be governed is reflected in the political arena and the system converges to the ideal definition of democracy. Thus, we can say determiningthe lower ages for voting and including the people in the elections regardless of their economic conditions and social status may contribute the democratic character of the system.

On the other hand, the effect of the votes on the outcome of the election is as important as the suffrage rate. The rules of electoral system may be defined concerning different aspects of the political life ranging from the political stability and rapidity in the decision making process to the comprehensiveness of the various fractions of the society regardless of how marginal they are. Hence, the countries may adopt different rules for counting the votes and set a certain level of threshold also effecting the distribution of votes in line with the political priority (Norris, 1997). In that case, one can say the more votes are valued and taken into account for establishing the governing office, the more democratic the political system gets. The general perception is that the small fractions in the government might diminish the effective decision making process, undermine the political stability at a certain level and thus emerge a weak impression in both the domestic and international arena. Hence, expecting the reflection of the votes on the composition of the governing body perfectly would be too much idealistic.

Regarding this issue, the heated debate about the height of the electoral threshold in Turkey constitutes one of the most relevant example. On order to be represented in the parliament, each political party should pass the %10 of the nation-wide votes. The current electoral system is inherited from the 1980 military coup. Since there had experienced the instability resulted from inability of the small parties to form a stable government, after the coup the electoral system has changed and the high threshold was adopted in order to exclude the marginal political parties and obtain a certain level of stability. However, especially in the last decade, the threshold began to undermine the fair representation of the public interests in the parliament. In the 2002 general elections in Turkey, only two parties out of 18 which ran in the elections could manage to enter in the parliament. At that elections, he victorious Justice and Development Party and the Republican People’s Party took the 66% and 33% of the seats in the parliament despite having only 34% and 19% of the national votes in fact. Moreover, the smaller parties which could not pass the national threshold were able to gain the landslide majority of the local votes. Then the small parties applied a different strategy and they dissolve themselves as party and form a loose and informal association among themselves to enter the elections independently since the independent nominees were allowed to race by only local votes and not required to pass the national threshold. This strategy was succeeded and the formation of the assembly has changed in the later elections. Nonetheless, the underrepresentation issue remained to be a problem regarding the comparison of the level of the threshold in Turkey and its one of the main political partner the EU to which it is the candidate member. The unrest is evident from the criticism coming from the various domestic institutions as well as the international ones. (Alkin, 2011) Thus, we can conclude that if we further analyze the government formation systems, the qualifications that the electoral system is bearing might pull down the level of democracy in the country.

At this point, we should elaborate the competition in the elections. In a democratic system, people expect to be provided the right to vocalize their opinions regarding the polity, especially when they are entirely different from the ones belonging to the current political power. Moreover, they expect to have the liberty to second the similar thoughts, engage in a joint action to promote these opinions and finally establish an organization to act collectively and formally to run for the office. Thus, the political parties and the pressure groups are indispensable parts of an electoral system.

On the other hand, in a broader perspective, the association is not limited with the political parties running in the elections. Particularly in the recent years, parallel to the developments in the information technologies, there emerged some the civic associations who are specialized in monitoring the voting and counting processes during the elections so as to ensure the transparency and fairness of the elections. For example, “Oy ve Ötesi Derneği” (Vote and Beyond Association) founded by the volunteers to monitor the electoral process during the municipal elections in 2014 in Turkey is one of such initiatives. The aim of the organization is to prevent the miscalculations of the votes that might be resulted either from an error while processing the data or a fraudulent motive. (http://oyveotesi.org)

Once we set the free and fair elections as the basic distinction between an authoritarian and a democratic ruling, we may assess the democracy level of the system by analyzing the formation of the electoral system in connection with the other liberties as explained above. Nonetheless, if the democracy is to be sustainable, the authority, even if it has been shaped through elections, should be allowed to exercise the power within certain set of rules.

DEMOCRACY BEYOND THE ELECTIONS: RULE OF LAW

In order to establish a democratic governing system, the transparency in the decision making process and the predictability of political and legal results of the decisions are expected. The key concept to ensure the transparency and also the legitimacy is considered to be the rule of law. Although the term also needs to be defined thoroughly, here it is used as the predictability and the generality of the rules that each and every person constituting the society should be bound with equally as long as the cases on which the norms are to be applied are showing equal features. Considering that the sustainability of the democratic order depends on accepting the plurality and the equal chance for joining in the electoral competition, the rule of law is the insurance the democratic system.

Institutionalizing of the electoral system guarantees the viability of the democratic order. Determining the eligibility of the people or associations that are competing in the elections is the first aspect of the proper functioning legal system. As the level of codification of rules regulating the elections is expanded, the transparency and the credibility of the elections are increased.

On the other hand, identifying the duty of the legal mechanisms as protecting the rules of the game of democracy has two symmetrical sides. One is to protect the governing power of the elected body vis-a-vis the other formal institutions such as military and bureaucracy or the informal ones, such as a religious sect or private company which might gain excessive influence in time. These structures have a certain degree of power in the sociopolitical system. However, in a democratic order, the people’s choice, which is the elected governing body, is expected to reign over the other fractions. In other words, in a democratic system, the elected body owns a true governing power (O’Donnell, 1996).

Second duty of the proper legal system is the mirror image of the first one, which is the protection of the government. The governing authority, even if it is established by the popular vote, should be allowed to exercise the power in certain boundaries. There is needed additional checks and balances system, other than the regular elections, to prevent the excessive arbitrary attitude of the governing authority between the election terms. This aspect of the legal system is also prevents the In order to assure the democratic rights, a properly functioning judiciary system should be established.

THE ROLE OF CULTURE ON THE LEVEL OF DEMOCRACY

Sociopolitical culture plays an important role in defining the level and features of democracy in a country. The differences between the systems which are commonly labeled as polyarchy basically emerges from the tools that are used by the political actors to sustain or advance their current status in political life. The selection of these tools are closely connected with the communication style between the governing bodies and the people as well as the one among the people of the country. That leads us to the effects of the overall culture in a country on the political life.

In a country where the government is established through competitive elections, the fractions running for the office are required to address the voters need and expectations. In the conservative countries these expectations are cumulated around the sentimental values while in the more liberal countries where the individualism come to the fore, the economic promises and respect to the private space of the individuals take credits. Thus, the tools of the political actors and the sytle of demanding of the people varies according to the culture.

People’s willingness of participation in political life is another important element that effects the democratic status of the society. The people who separate their personal and social space distinctively are more likely to engage in politics comparing to the people who put the general social order in the first place of their priorities. The former category of people are more eager to defend and advance their private interests. Another component in this issue is the people’s perception of the authority. If a person sees the authority as a superior power with full capacity and capability of handling the problems and needs of the society, in simpler words, has an hierarchical sight about the government, his/her tendency towards engaging in the political struggle is observed at lower levels. By contrast, if the person perceives the governing body as his/her equal in terms of problem solving capacity, then the person’s motivation to express his/her opinions. (Shi, 2015) Thus, the domestic demand for democracy is generated by the interaction among the people who have different types of perception.

PRACTICAL NEED FOR DEMOCRACY

The efforts exerted to define democracy also serve a practical need of the political actors. The political success and occupying the governing office provides an access to the resources exceptionally. However, the authority which has such privilege also needs a legitimate ground. In an autocratic regime, the legitimacy sources from the divine or dynastic codes while in the polyarchies it rest in the people’s choices. The ruling power is expected to take the decisions complying with the people’s will. The continuation of governing power in a democratic system depends on the promise that the democratic order will prevail and people will continue to be at the center of the decision making mechanism. We may put the democracy is a self-generating system and the political actors needs to prove themselves loyal to the system to continue their positions.

There are the domestic and international aspects of the legitimacy issue. (O’Donnell, 1996) Degree of harmonizing the actual behaviors and the formal rules assures the popular support that creates the domestic legitimacy. On the other hand, the governments need the international legitimacy as well to survive in the complex relations of the global society. Since the contemporary world order necessitates the intensive interaction, the level of sociopolitical inclusion is regarded as a positive feature of the regime. Thus the definition is manipulated in terms of including or excluding the variables to fit the term with the political reality in order to create a positive image.

CONCLUSION

As in the “ladder of generality” concept introduced by Giovanni Sartori, the more variables are considered, the less convergence can be found between the actual case and the expected style of democratic order (Collier and Levitsky, 1997). When we simplify the definition and focus on the procedural minimums such as free and competitive elections, freedom of speech and absence of massive fraud, we may include more countries in the democratic club.

Taking into account that the range of variables that should be considered to refer a system as democratic or not, we may conclude that the term “democracy” is rather like a scale that measures the level of participation in the decision making process. According to the aim of the research, one may focus on the level of democracy in the political field or at the social arena or in the economic life to simplify the analysis. On the other hand, they are all interconnected parts of the society. In order to reach the complete picture of democracy in a society, in fact, all the variables at the different fields of the society should be taken into account. One last thing to be underlined is that the inclusion or exclusion of certain aspects in the definition of democracy can occasionally be a political or at least sentimental decision whenever the aim of the analysis is to label an actual system as democracy or not. In the end, the difficulty in finding a fixed definition for democracy is sourced from the complexity of the interaction among the people.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shi, Tianjian, 2015. The Cultural Logic of Politics in Mainland China and Taiwan. NY: Cambridge University Press. Ch. 6.

Collier, David and Steven Levitsky. 1997. “Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research.” World Politics 49 (3):430-51.

O’Donnel, Guillermo, 1996. “Illusions About Consolidation.” Journal od Democracy 7.2, 34-51. Norris, Pippa, 1997, “Choosing Electoral Systems: Proportional, Majoritarian and Mixed Systems.”

International Political Science Review (Contrasting Political Institutions special issue), Vol 18(3): 297-312.

Sinan Alkin, 2011. “Underrepresentative Democracy: Why Turkey Should Abandon Europe’s Highest Electoral Threshold”, 10 Washington University Global Studies Law Review. Vol. 10(2): 347-369, http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol10/iss2/5